In a showdown between fast cars and slow-moving turtles, the losers are easy to spot, flattened on increasingly busy roads. The study of this often deadly interaction of road networks and nature is called road ecology.

In a showdown between fast cars and slow-moving turtles, the losers are easy to spot, flattened on increasingly busy roads. The study of this often deadly interaction of road networks and nature is called road ecology.

Some background reading I’m doing for a project includes a guide billed as a “resource for students, citizens, government and non-government agencies.”

If you produce material that you hope will be read and understood, you can use readability tests to get an idea of how you’re doing. I ran some tests on a section of the guide to see just how easy it is to read.

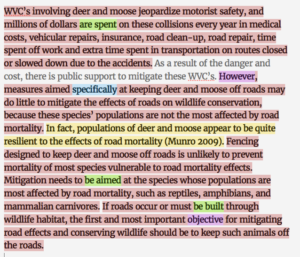

Here’s one paragraph — with danger zones highlighted by the Hemingway app — headlined “Direct Mortality: Wildlife/Vehicle Collisions (WVC’s).” (Ugh. If you had to use the awkward WVC instead of simply spelling out “collisions,” the plural does not take an apostrophe.)

A readability test shows this section has a grade level of about 16, making it understandable by 21- to 22-year-olds. There are 39 complex words (like mitigation), nearly 20% of the total 198 words. Average number of words per sentence is 28.29 (9-18 are best). Reading ease is 37.6 (you want 60 or more). The Hemingway app shows that only one sentence isn’t hard to read, and three are written in the passive voice.

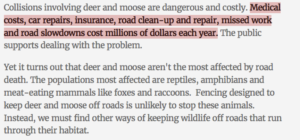

I rewrote the lengthy paragraph and split it in two, aiming for simpler words and shorter sentences, in my newsletter, Wordnerdery.

The rewrite meets a grade level of about 10, making it easily understood by 15- to 16-year-olds — and busy, impatient readers. There are 12 complex words, about 12% of the total 98 words. Average number of words per sentence is 14, about half of the original text. Reading ease is 65.7. The second sentence is the only one considered very hard to read, and there is no passive writing.

If a readability test shows a piece of writing could be improved, follow these nine steps:

- What point are you trying to make? Start with that in mind.

- Shorten words, aiming for an average of five characters per word; “death” instead of “mortality,” for example.

- Cut out unnecessary words, such as “specifically.”

- Break separate thoughts into separate sentences.

- Tighten and shorten sentences. Aim for an average of 14 words per sentence, which results in 90-99% understanding, according to the American Press Institute. A sentence of 28 words will be understood by only 50-59% of readers.

- Break paragraphs into fewer sentences, averaging just two or three.

- Make lists or bullet points if needed.

- Write to the reader (“you”).

- Use active vs. passive writing (“cost millions of dollars” vs. “millions of dollars are spent”).

Do you have an effective “before and after” piece of writing? Do share. And let me know if you’d like help making your own content more readable.

Wordnerdery is a quick read about words, effective/expressive writing, newsletters and more. Are you a subscriber yet? If yes, thanks for reading! If not, you can sign up right now. In keeping with Canada’s anti-spam laws, you can easily unsubscribe any time.